2011 February

MOVE, Choreographing You at The Hayward Gallery, London, & Haus der Kunst, Munich

On 02, Feb 2011 | In blog | By selene

First appeared in German Translation in Artline, 12.02.2011

Original text & translation by Selene States

Mike Kelley Room, 2011 © Hayward Gallery.

MOVE, Choreographing You transects the fields of art and dance, charting artistic practices involving choreography over the last 50 years. Its first point of departure is the convergence of art and dance in the late 1950s and early 60s, when practices shifted from a representational to a performative idiom. Artists began to direct the movements of gallery visitors with sets of instructions (e.g. Kaprow’s ‘Happenings’) while dancers “maintained a seemingly obdurate disregard for audience expectations, eschewing music, spectacle, innate kinetic gifts and acquired virtuosity to challenge questions of the nature of self-presentation.” 1

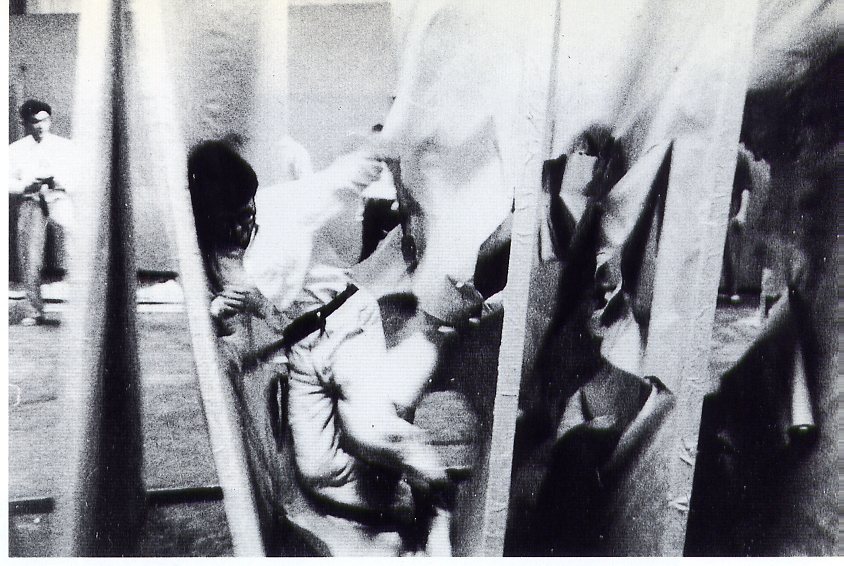

The exhibition hosts an extensive digital archive of performance art and dance from this period with a compellingly navigable interface, which in itself justifies a visit to MOVE. Its canon of 1960s and 1970s video works, with artists such as Carolee Schneeman, Rebecca Horn, Bas Jan Ader, to name a few, are supplemented by documentary footage of dance performances from the 1950s to the present, photographs of the Gutai Movement 2, and digital facsimiles of sketches for Kaprow’s Happenings.

Saburo Murakami Lacerations of Paper, 1956 © Saburo Murakami.

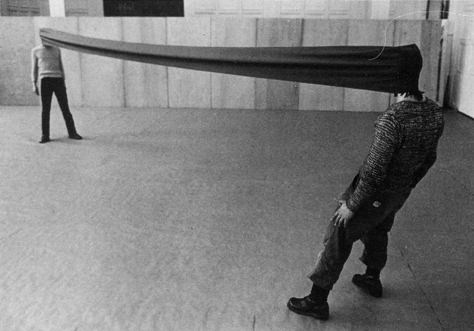

Although the archive’s digital interface promotes physical inertia, (I spent the first hour and a half immersed in the virtual catalogue), the rest of the exhibition invites the audience to engage with artwork on a very corporeal level. As the exhibition title suggests, the imperative is to move the visitor. The installations are mobile and climbable, objects demand to be handled and touched. Bruce Naumann’s Green Light Corridor (1970) forces the viewer to move between a narrow corridor for an immersive experience of green neon lights. Franz Erhardt Walther’s Körpergewichte (1966), a long band of cloth, invites two gallery visitors to sling the object around their waists and lean back for counterbalance at about four meters distance, while his Für Zwei (1967), a rectangular canvas with two large holes cut in it, suspends two viewers face to face, a few inches apart. These physical prompts activate the viewer in a discursive space of conversation, generating different sets of meaning according to the relations between individuals. Naturally, the interactions between a set of strangers confronted with the awkward intimacy of Für Zwei, or expected to trust one another with their weight in Körpergewichte, will be very different to the encounters between two lovers face to face or in a tug-of-war.

Franz Erhardt Walther Körpergewichte, 1966 © Franz Erhardt Walther.

Franz Erhardt Walther Körpergewichte, 1966 © Franz Erhardt Walther.

Dancer and Sculptor Robert Morris’ Bodyspacemotionthings (See-saw) (1971/2010), is a rectangular wooden platform the size of a double mattress, balanced on a half-sphere. As gallery visitors teeter back and forth, the piece literally moves the viewers, concretising the exchange between Morris’ contemporaries Donald Judd and Michael Fried, whose 1965-67 discourses incited the viewer to occupy a performative space in relation to the object. As the title of the work suggests, Bodyspacemotionthings (See-saw) encompasses the entire set of situatiotional relations between the subject and object, as well as the conditions of space, motion and time. Here, objecthood expands as a set of relations, and the playful outcome is a see-saw of subject and object.

See-saws are not the only reference to child’s play: the exhibition is a veritable obstacle course of interactive play stations: Hula hoops, monkey rings, and a labyrinthian fun-house. Mike Kelley’s Room containing mutiple stimuli known to elicit curiostiy and manipulatory responses (1999), includes a monkey suit and a jungle gym. Mike Kelly’s Room encourages us to monkey around, making a spectacle of ourselves, and provides us with a model of human behavioral inhibitions and norms. Gallery visitors can improvise and play on the structures, test their balance and coordination, and entertain naive childish curiosity. And playground behavior does abound. While traversing William Forsythe’s The Fact of the Matter, (2009) the gallery attendant condescendingly applauded me for being the first woman to complete the course that day!

William Forsythe The Fact of the Matter 2009 © Forsythe Company with the Biennale Art Venice and the Ursula Blickle Foundation.

William Forsythe The Fact of the Matter 2009 © Forsythe Company with the Biennale Art Venice and the Ursula Blickle Foundation.

In a contemporary context, in which ‘interactive installations’ are almost ubiquitous, most of these works engender an interpretation of choreography, where the imperative is not to ‘move to action’, but just to play. While both action and play may engage the viewer in movement, they have very different motivations. Unfortunately, MOVE provides the viewer with too few anchor points to the historical context. A plethora of concurrent aesthetic tactics of the 1950s and 60s, practised by artists from Rainer to Guy Debord, from Kaprow to John Cage, called for the viewer’s will to agency, rather than spectatorial passivity. Their work not only called the viewer to action through choreography, but incited a new kind of body politics, emerging at a time of pervasive political action.

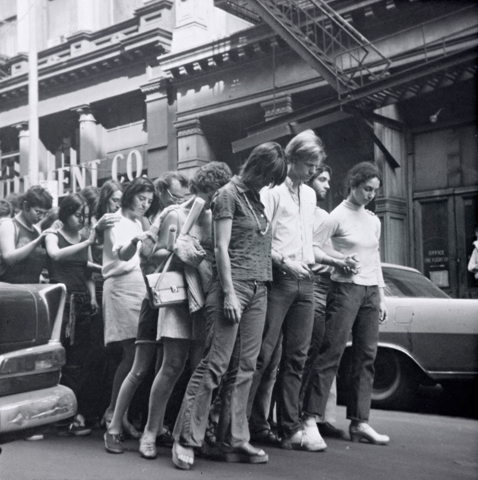

Yvonne Rainer’s Street Action (1970) and Trio A with Flags (1970) choreographed large numbers of individuals in acts of political dissent. Critique through aesthetic gesture had its immanent equivalent in dissent and political action. Alongside the student movement, civil rights movement, anti-war movement and women’s liberation movement, artist activists were calling to action and political protest. The curators of MOVE efface the trajectory from “move” to movement, action to activisim. The imperative “MOVE” is never qualified: should we move up? down? aside? move beyond, to the left or to the right?

Interacting with dancers, other visitors, and the immersive virtual archive at MOVE was an enjoyable and animating gallery experience. But so much is missing from MOVE’s white-cube canonisation of radical practices that set the stage for the body and identity politics of performance art. The curatorial choreography tip-toes around the difficult task of situating these works politically, robbing them of their gravity, and suspending MOVE in a peculiar state of stasis.

Yvonne Rainer Street Action (M-Walk), 1970, with Yvonne Rainer, Douglas Dunn and Sarah Rudner © The Getty Research Institute.

2 predating similar artistic tactics in the West by several years.

Recent Comments